“However, do not rejoice that the spirits submit to you, but rejoice that your names are written in heaven.” Luke 10:20

Japanese seem to have a particular affinity for record keeping. We first noticed this tendency at construction sites, where a worker would routinely pose in front of a project for a picture while holding a chalk board. On that board would be written the date and a brief description of the work they had just completed. The job might involve something as minor as repairing a pothole in the road, but photographic evidence of the completed project was duly recorded. The picture was then probably submitted with a report and filed somewhere with millions of other similar items within the black hole of Japanese archives.

Recording and keeping essential information is a mainstay of modern civilization, but Japan appears to have a particular penchant for this activity. For example, parents are expected to submit regular reports confirming that their children completed assigned homework. During the summer, such reports are expanded to include personal hygiene practices and chores around the house to ensure the maintenance of important routines during school holidays. Zealous new parents can purchase “baby diaries” to record essential information, such as the frequency of diaper changes, bottle feedings, daily temperatures, physical growth, appearance of teeth and the introduction of different foods into the baby’s diet.

Precise record keeping is considered essential for tracking even the most minor lost items. Upon being turned in, the items are routinely tagged, numbered, and documented with the hope of returning them to the rightful owner. Minutes are scrupulously taken at every meeting and there seems to be a form for everything that must be completed and then put on file. As a young church planter, I soon discovered that I was expected to keep a record of everything that took place at the church for future reference. In so doing, I also became a cog in the vast machine storing information for generations to come.

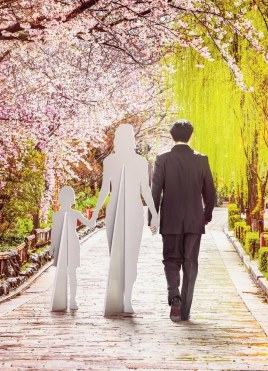

When the seventy-two disciples Jesus sent out returned from their initial ministry experience, they were understandably excited to report the details of what they had seen and experienced (Luke 10). As we constantly engage with life, experiencing its highs and lows, we are naturally inclined to become preoccupied with the details of this world and, consequently, often fail to appreciate the significance of the world to come. This is where Jesus’ reply to His early followers (“do not rejoice that the spirits submit to you, but rejoice that your names are written in heaven” Luke 10:20) serves to put such things in perspective and helps us not to lose sight of the forest of eternity as we wander among the trees of daily life. While we may be inclined to get overly excited or overly disappointed with the details of this life, we should never forget that our names are recorded for eternity in heaven. This means that all that we do, all that we value and all that we experience is grounded in an eternal relationship with God that can never be erased. Our lives have meaning and all that we offer up to God in our worship of Him is recorded for eternity. That is certainly a cause for much rejoicing.